Living Between Two Cultures

France resolute on change as mass walkout cripples country

The Associated Press

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

PARIS: Civil servants, from teachers to postal workers, began a mass walkout across France on Tuesday, the seventh day of a transport strike that has caused havoc on French rails. But the government said it would not abandon its planned changes.

Up to half of the country's teachers could stay off the job in support of higher salaries and job security, officials have said. Postal and tax services were also affected. Flight disruptions were expected, as air traffic controllers are also civil servants.

National newspapers were absent from the streets Tuesday as printers and delivery personnel joined the strike.

Though not state workers, they used the opportunity to protest job cuts.

With a paralyzing transit strike stretching toward its eighth day, Ludovic Boltz, a commuter, stood in the gloom on a suburban train platform Monday, fuming about his daily journey and shaking a bag of baguettes in fury.

"My opinion of this strike is that it's annoying lots of people and lots of workers," he said, voice rising above a bellowing announcement of another train delay. "It amounts to terrorism, and we're the hostages."

But there was no relief in sight to ease the commuter misery from the national transport strike that the government says is costing the nation from €300 million to €400 million, or $444 million to $591 million, a day. On Monday, rail workers voted to press on with the strike, most likely at least through Wednesday, when union officials will sit down with government officials and transportation executives for talks.

November is shaping up as the high season in France for strikes, with students challenging a new higher education law, tobacco shop owners organizing to demonstrate against a new anti-smoking law and French judges and lawyers poised for a Nov. 29 strike to protest structural changes that could result in the elimination of 200 courts.

Along the train platforms, weary resignation with limited services is starting to turn into resentment as the crippling strike continues. On Sunday, several groups organized a counterdemonstration in eastern Paris to demand an end to the conflict.

The governing party, the UMP, has been passing out fliers at train stations denouncing rail workers as a "minority defending a system of retirement at two speeds."

"People are really fed up," said Sabine Herold, a spokeswoman for a group called Liberal Alternative, which helped organize the stop-the-strike rally in Paris. "It's very complicated with the subway, buses and trains blocked. It's very difficult to have a normal life. People are really fed up because they think the strikers are egotistical."

The rail unions are fighting to keep special privileges for about 500,000 workers that grant locomotive drivers, for example, the option of retiring at 50 or 55 with full pension benefits. The government wants the workers to pay into the retirement system for at least 40 years, changes that have already taken place for workers in private industry and the civil service.

On Sunday, the stop-the-strike demonstration drew about 8,000 people, according to the police, or 20,000, according to organizers, who noted that people had braved bitter cold to participate, along with a general lack of transportation.

It was hardly the turnout of May 1968 when a huge showing of the "silent majority" converged on the Champs-Élysées to demonstrate support for President Charles de Gaulle, who was confronting student unrest.

But Herold said the group had united with others to organize another rally for next Sunday if the strikes continue. Others in her group, like Jean-Paul Oury, said they considered the counterdemonstration over the weekend just the first round.

Polls show that the counterdemonstrators are tapping into popular sentiment, with a majority of the French people siding with President Nicolas Sarkozy on changes in the pension system.

A weekend poll by Ipsos, commissioned by the government, found that support for changing the pension system had grown 10 percentage points to 64 percent in one week, while support for the strikers had dropped from 35 percent to 33 percent.

Ellen and I rode the Batobus, a boat shuttle which runs in a loop on the Seine. Since I'm writing about the river for this research project, I thought I needed to get out on it. Paris looks a little different from the water. You get a new perspective on buildings, monuments, and the whole city. We saw things we had never noticed before.

Ellen and I rode the Batobus, a boat shuttle which runs in a loop on the Seine. Since I'm writing about the river for this research project, I thought I needed to get out on it. Paris looks a little different from the water. You get a new perspective on buildings, monuments, and the whole city. We saw things we had never noticed before.

Here's Ellen puzzling over the map of the Louvre. We went today to see the 19th century French paintings and a show of Biedermeier furniture, among other things. It was cold and rainy as we left one of our favorite restaurants, Le Loup Blanc, but we made it home on foot. The strike is still on with no end in sight. However, we checked the internet, and the trains to Switzerland may still be running. We'll have to see.

Here's Ellen puzzling over the map of the Louvre. We went today to see the 19th century French paintings and a show of Biedermeier furniture, among other things. It was cold and rainy as we left one of our favorite restaurants, Le Loup Blanc, but we made it home on foot. The strike is still on with no end in sight. However, we checked the internet, and the trains to Switzerland may still be running. We'll have to see.

Ellen made it to town last night after a 3 hour van ride from the airport. The strike is still on, so traffic was worse than normal, and apparently she was the last stop on the driver's list. But I treated her to a nice dinner out at one of our favorite restaurants (Le Gai Moulin), and she slept late this morning. Here she is having an afternoon pick-me-up following our trip to Le Grand Palais to see an exhibition of Gustave Courbet's artworks.

Ellen made it to town last night after a 3 hour van ride from the airport. The strike is still on, so traffic was worse than normal, and apparently she was the last stop on the driver's list. But I treated her to a nice dinner out at one of our favorite restaurants (Le Gai Moulin), and she slept late this morning. Here she is having an afternoon pick-me-up following our trip to Le Grand Palais to see an exhibition of Gustave Courbet's artworks.

Paris is a city of layers, many of which you can see right before your eyes. This building on the rue Francois Miron demonstrates this principle well. It dates from the early 16th century, but its earliest components go back to the 14th century. Restored in the late 1960s, it remains one of the few surviving examples of Medieval domestic architecture in the city. Of course it's surrounded by much more modern construction from the 19th and 20th centuries -- hence the layers.

Paris is a city of layers, many of which you can see right before your eyes. This building on the rue Francois Miron demonstrates this principle well. It dates from the early 16th century, but its earliest components go back to the 14th century. Restored in the late 1960s, it remains one of the few surviving examples of Medieval domestic architecture in the city. Of course it's surrounded by much more modern construction from the 19th and 20th centuries -- hence the layers. The strike continues today, and as a result there are many more bikes on the street as people try to find alternative ways of getting around the city. But even without the strike, the people-to-bike ratio had already increased thanks to the Velib, the city's new bicycle rental service. For a modest fee, you can sign up for this program, and any bike you check out from one of the many stands around town is free for the first 30 minutes. As a result, there are more Parisians on wheels.

The strike continues today, and as a result there are many more bikes on the street as people try to find alternative ways of getting around the city. But even without the strike, the people-to-bike ratio had already increased thanks to the Velib, the city's new bicycle rental service. For a modest fee, you can sign up for this program, and any bike you check out from one of the many stands around town is free for the first 30 minutes. As a result, there are more Parisians on wheels.

The ferris wheel at Place de la Concorde has been up ever since I got here. I haven't ridden it, but I'm sure it provides a great view of the Champs-Elysees and the Louvre since it sits right between them.

The ferris wheel at Place de la Concorde has been up ever since I got here. I haven't ridden it, but I'm sure it provides a great view of the Champs-Elysees and the Louvre since it sits right between them. The Bastille column sits on the site of the old Bastille prison which was torn down in 1789 at the beginning of the French Revolution. It actually commemorates another revolution -- the Revolution of 1830 -- when the French, once again, overthrew their king. Today, it remains a site of popular protest when people want to make their voice heard in Paris. But at night, that symbolism gives way to the beautiful illumination of the column against the sky.

The Bastille column sits on the site of the old Bastille prison which was torn down in 1789 at the beginning of the French Revolution. It actually commemorates another revolution -- the Revolution of 1830 -- when the French, once again, overthrew their king. Today, it remains a site of popular protest when people want to make their voice heard in Paris. But at night, that symbolism gives way to the beautiful illumination of the column against the sky. Even as the weather gets chillier, the Paris flower market continues. Located on l'Ile de la Cite not far from Notre Dame, it's the kind of thing that's easy to miss because it's surrounded by more famous landmarks. But Parisians love their flowers, whether in the parks or on the corner flower shops that you can find in nearly every neighborhood. And everyone can find something they like at the flower market.

Even as the weather gets chillier, the Paris flower market continues. Located on l'Ile de la Cite not far from Notre Dame, it's the kind of thing that's easy to miss because it's surrounded by more famous landmarks. But Parisians love their flowers, whether in the parks or on the corner flower shops that you can find in nearly every neighborhood. And everyone can find something they like at the flower market. One of the changes I've noticed most during this trip to Paris is the number of Parisians who jog. In the past, only the Americans jogged, or if the French did, I only saw them in one place, the Parc Montsouris on the southern edge of the city. But now, I see Parisians jogging in the street and in several parks. I've even seen groups of high school students running laps around the Jardin du Luxembourg urged on by a coach with a whistle. I don't think of Parisians as joggers, so this has been something of a strange sight.

One of the changes I've noticed most during this trip to Paris is the number of Parisians who jog. In the past, only the Americans jogged, or if the French did, I only saw them in one place, the Parc Montsouris on the southern edge of the city. But now, I see Parisians jogging in the street and in several parks. I've even seen groups of high school students running laps around the Jardin du Luxembourg urged on by a coach with a whistle. I don't think of Parisians as joggers, so this has been something of a strange sight.

Paris is full of memorials and monuments, but this one is particularly interesting. It's a monument called the "Flame of Liberty" that commemorates the French government's donation of the Statue of Liberty to the US. But its location has caused it to be turned into something else. It sits at the Place de l'Alma, just above where Princess Diana's car crashed 10 years ago. So, it has become an informal, impromptu monument to her. You can see the picture of her plastered to the side of the pedestal and the flowers, notes, pictures and other mementos left there by admirers. I'm sure there are always things which people place there in memory of her, but given that this is the 10th anniversary, they've probably been putting more things there than usual.

Paris is full of memorials and monuments, but this one is particularly interesting. It's a monument called the "Flame of Liberty" that commemorates the French government's donation of the Statue of Liberty to the US. But its location has caused it to be turned into something else. It sits at the Place de l'Alma, just above where Princess Diana's car crashed 10 years ago. So, it has become an informal, impromptu monument to her. You can see the picture of her plastered to the side of the pedestal and the flowers, notes, pictures and other mementos left there by admirers. I'm sure there are always things which people place there in memory of her, but given that this is the 10th anniversary, they've probably been putting more things there than usual.

I first read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road ten years ago during my first trip to Paris. It was the book’s 40th anniversary, and I read an article about it on an in-flight magazine. That, plus the fact that a friend had recommended it to me and that I kept seeing it in bookstores, led me to buy it in London’s Gatwick Airport. I still have the cash register receipt, yellowed and creased, tucked into the book. So I know that I read the first words of the book -- “I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up....” -- on September 21, 1997. I thought, “Hey, I’m on the road too,” and plunged into a book that, it turned out, would change much about the way I thought.

When I first read Kerouac, I was struck by the sense of adventure, fun, and excitement of being on the road -- something I felt then too being in Paris for the first time. For Sal and Dean and the other characters in the slightly-fictionalized version of Kerouac’s own travels in the late 1940s, the goal was having “kicks” and seeing what lay ahead on a road that stretched out beyond where the eye could see. The theme that I paid most attention to was their desire for experience, life, and exploration. They couldn’t seem to explore enough, both of America and of themselves.

Those two were, metaphorically, the same thing. Sal and Dean are “all-American” boys, although not the sort from 1950s sitcoms. Dean -- based on the real-life Neal Cassidy -- is a former juvenile delinquent and ex-con, a feverish talker, crazy driver, and con man who thinks of little but himself. He is plagued by “madness,” something which Kerouac never labels or describe any further, but seems to be a cross between ADD and existential angst. Dean is endearing in many ways too. Throughout the book, he pulsates with energy and literally says “Yes” to everything and everyone he meets. His life may be troubled, but it’s certainly full to the brim.

Sal -- the fictionalized Kerouac himself -- is quieter, shyer, more reflective and broody. He embraces an America that is similarly “beat” -- the word that he popularized. “Beat” means down-and-out, but it takes on tones of mystical revelation. Drawing on his Catholic heritage, Kerouac’s “beatness” meant being beaten down to the point of seeing things in a new way, of removing all your old self and creating a new one. Beat revelation could lead to resurrection. And that’s the America Sal sees.

One of the things I loved most about this book when I first read it was that he captures of a vision of post-WWII America that is not the one of economic good times, the baby boom, and suburban white picket fences. There is no nuclear family, no new car in the driveway, and no mom vacuuming in high heals and pearls. Instead, there are migrant farm workers in California picking fruit, black jazzmen blowing in juke joints, bums riding the rails and warming themselves around fires, and the “beat generation” of bohemian writers like Kerouac, Alan Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and others before they became the famous icons of modern American literature. They are Kerouac’s heroes because their outsider status -- and their “beatness” -- means that in his eyes, they are closer to some greater truth than all the people who follow the rules and do what they’re told. The “beat” have nothing to lose because they’re already society’s losers. That makes them “the poor in spirit” to whom belongs the kingdom of heaven.

That notion of loss runs throughout the book as Sal and Dean search for “IT,” as Dean calls that sense of revelation, but which they rarely ever find. Dean is constantly looking for his long-lost alcoholic father who has abandoned him, and Kerouac ends the novel by conflating the two men. The book’s last words are: “...I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.” The sense of absence permeates Sal and Dean’s relationship. The climax of the novel comes at the moment and in the place where Sal and Dean come closest to the freedom and inspiration for which they’ve been looking as they encounter a limitless sensual and emotional experience in Mexico, a place they see as being free of strictures and limitations of American society. Kerouac calls it “the end of the road.”

Sal loses more than his friend, he loses his illusions about life and love. He still embraces a romantic vision of “beat America” where the downtrodden are more real and true than the mainstream and the road still beckons to him as the path to a mystical journey. Later novels carry on this theme of travel as redemption and enlightenment. But it’s the human story of the ending of his friendship with Dean that made its powerful punch to me this time.

The other theme, related to the first, that became more apparent to me on this reading was the loneliness of the road which Sal feels, especially in the first part of the book. On his first journey when he crosses the US by himself, he meets many people and has a range of interactions. But there are long stretches of solitude too. For all the connections he makes, each one leads to an eventual departure and to having no one on whom to rely but himself.

The best example is his encounter with Terry, the Mexican girl he meets on the bus to California. They start a relationship and almost see themselves as married for a time. Their feelings seem genuine, and he moves to be with her family and picks fruit with them in the hot sun. There, he dreams of being a Mexican -- a fantasy full of romantic stereotyping which bears little resemblance to the real lives these people lead. But, despite the intensity of his feeling for Terry and the time he spends with her, he knows that it has to end. And it does. The road remains open -- it beckons to him -- but often he’s the only one on it.

I think markets like these (this one is on the Boulevard Raspail) are one big reason why Americans like Paris. We have farmers' markets in the US, but somehow the outdoor markets in Paris seem more exciting. For one thing, the food is always fresh, and it's all out there for you to see. And there are things you will never see in the US -- for instance the hare (with blood-stained fur still on -- now that's fresh!) and pheasants in one of the photos. The French seem to have no problem putting raw meat out on display without refrigeration. The varieties also seem endless. Dozens of cheeses, breads, vegetables, cuts of meat, nuts, seafood (including whole octopus), and anything else you want. People pull their little shopping carts along the sidewalk which is now turned into the central aisle of one of the world's best grocery stores. Vendors sometimes call out with information about their wares. One sang a song. It's a real neighborhood event.

I think markets like these (this one is on the Boulevard Raspail) are one big reason why Americans like Paris. We have farmers' markets in the US, but somehow the outdoor markets in Paris seem more exciting. For one thing, the food is always fresh, and it's all out there for you to see. And there are things you will never see in the US -- for instance the hare (with blood-stained fur still on -- now that's fresh!) and pheasants in one of the photos. The French seem to have no problem putting raw meat out on display without refrigeration. The varieties also seem endless. Dozens of cheeses, breads, vegetables, cuts of meat, nuts, seafood (including whole octopus), and anything else you want. People pull their little shopping carts along the sidewalk which is now turned into the central aisle of one of the world's best grocery stores. Vendors sometimes call out with information about their wares. One sang a song. It's a real neighborhood event.

Today is Toussaint -- All Saint's Day -- and everyone goes to the cemetery to visit their friends and family members who have passed on. I went to the Montparnasse cemetery and saw people cleaning graves and planting flowers (as in the photos) and reflecting quietly. A few tourists looked around too since the cemeteries of Paris are always a popular sight. They're a calm and peaceful place in the middle of a busy city, and they're so different from most American cemeteries with their enormous monuments and sculptures.

Today is Toussaint -- All Saint's Day -- and everyone goes to the cemetery to visit their friends and family members who have passed on. I went to the Montparnasse cemetery and saw people cleaning graves and planting flowers (as in the photos) and reflecting quietly. A few tourists looked around too since the cemeteries of Paris are always a popular sight. They're a calm and peaceful place in the middle of a busy city, and they're so different from most American cemeteries with their enormous monuments and sculptures. I think it's a relatively recent phenomenon, but the French celebrate Halloween too. When I first came to Paris 10 years ago, I remember seeing people in costume on the Metro that night. Last weekend, I saw people walking around in costume too, perhaps going to early Halloween parties since the day falls mid-week this year. I saw these boxes of candy in a shop a few days ago as people prepared for the day. I'm not sure if they go Trick or Treating, though.

I think it's a relatively recent phenomenon, but the French celebrate Halloween too. When I first came to Paris 10 years ago, I remember seeing people in costume on the Metro that night. Last weekend, I saw people walking around in costume too, perhaps going to early Halloween parties since the day falls mid-week this year. I saw these boxes of candy in a shop a few days ago as people prepared for the day. I'm not sure if they go Trick or Treating, though.

I don't know how well you can see the photo (click to enlarge), but these are plaques on the walls in the Eglise des Blancs- Manteaux in the Marais section of Paris. Many of the churches here have such plaques, placed by people as a sign of thanks for prayers answered or lives changed. Undoubtedly, they also reflect a certain social status -- only those who could afford to pay were able to place such a plaque. But they are an interesting and lasting testament to the power of people's faith.

I don't know how well you can see the photo (click to enlarge), but these are plaques on the walls in the Eglise des Blancs- Manteaux in the Marais section of Paris. Many of the churches here have such plaques, placed by people as a sign of thanks for prayers answered or lives changed. Undoubtedly, they also reflect a certain social status -- only those who could afford to pay were able to place such a plaque. But they are an interesting and lasting testament to the power of people's faith.

I've never been to this restaurant, but I've heard of it many times, and when I walked past it the other day, I decided to take a picture of the sign. It's an American-style diner with American-style food. I suppose it caters to Americans longing for the kind of food they get at home and to French people who like to imagine that they're in the US. It also speaks of the fascination of the French with aspects of American culture, some of which you might not expect . Many Americans travel to France precisely for the food which they consider to be superior to US food. I wonder what they think when they see Breakfast in America?

I've never been to this restaurant, but I've heard of it many times, and when I walked past it the other day, I decided to take a picture of the sign. It's an American-style diner with American-style food. I suppose it caters to Americans longing for the kind of food they get at home and to French people who like to imagine that they're in the US. It also speaks of the fascination of the French with aspects of American culture, some of which you might not expect . Many Americans travel to France precisely for the food which they consider to be superior to US food. I wonder what they think when they see Breakfast in America?

Paris is not just a city of sights but also of smells. Walking through the Marais neighborhood, I encountered this fish market with both bright, beautiful colors and the smell of fresh seafood wafting out into the street. There are other smells too. A few weeks ago, I saw some beautiful mushrooms with a strong, earthy smell. The city itself smells too, as Ellen and I found out a couple of summers ago when we took the sewer tour.

Paris is not just a city of sights but also of smells. Walking through the Marais neighborhood, I encountered this fish market with both bright, beautiful colors and the smell of fresh seafood wafting out into the street. There are other smells too. A few weeks ago, I saw some beautiful mushrooms with a strong, earthy smell. The city itself smells too, as Ellen and I found out a couple of summers ago when we took the sewer tour. Coming back from the grocery store this afternoon, I encountered this band playing on the street. It was a father and his 2 sons, all joining in on some familiar American jazz and pop tunes. The older boy -- the one playing the trumpet in the photo -- sang as well. He was a bit shy about it, but I think it made his performance more endearing since it must take a lot of guts to stand on a Parisian street corner and sing -- with a microphone too. They weren't the most polished band I've ever heard (although they were pretty good), but they were definitely a crowd favorite. People gathered around and listened, clapped, and gave them money. You can't really tell in the photo, but the younger one is playing a little kid-sized keyboard.

Coming back from the grocery store this afternoon, I encountered this band playing on the street. It was a father and his 2 sons, all joining in on some familiar American jazz and pop tunes. The older boy -- the one playing the trumpet in the photo -- sang as well. He was a bit shy about it, but I think it made his performance more endearing since it must take a lot of guts to stand on a Parisian street corner and sing -- with a microphone too. They weren't the most polished band I've ever heard (although they were pretty good), but they were definitely a crowd favorite. People gathered around and listened, clapped, and gave them money. You can't really tell in the photo, but the younger one is playing a little kid-sized keyboard.

Ellen and I saw this last summer. I had looked for it again this year, but didn't find it until today. I still don't know why there is a large picture of the famous black radical activist Angela Davis -- in full 1970s militant mode, afro and all -- on the wall of a nice Left Bank Parisian neighborhood not too far from Le Bon Marche. But apparently, the French are taken with her. Last summer, Ellen and I saw some socks with her image on them (this same image, I think). Davis studied in Paris during her youth, so perhaps that's part of the connection. Maybe her image is like that of the famous picture of Che Guevara which has become such a commodity that it's on t-shirts, posters, and everything else. Che is probably turning in his grave -- how can you fight the system when you are co-opted by the system? I wonder what Angela Davis thinks?

Ellen and I saw this last summer. I had looked for it again this year, but didn't find it until today. I still don't know why there is a large picture of the famous black radical activist Angela Davis -- in full 1970s militant mode, afro and all -- on the wall of a nice Left Bank Parisian neighborhood not too far from Le Bon Marche. But apparently, the French are taken with her. Last summer, Ellen and I saw some socks with her image on them (this same image, I think). Davis studied in Paris during her youth, so perhaps that's part of the connection. Maybe her image is like that of the famous picture of Che Guevara which has become such a commodity that it's on t-shirts, posters, and everything else. Che is probably turning in his grave -- how can you fight the system when you are co-opted by the system? I wonder what Angela Davis thinks?

The Arcades of Paris are well-known to historians but sometimes missed by visitors. Essentially, Parisians invented the mall. In the early 19th century, they enclosed areas between streets to create new passageways which became important places to socialize and to see and be seen. Now, many of the arcades -- like this one just off of the Grands Boulevards -- have skylights and lots of little shops, boutiques, and restaurants. They're a nice respite from the street where you can still see interesting things.

The Arcades of Paris are well-known to historians but sometimes missed by visitors. Essentially, Parisians invented the mall. In the early 19th century, they enclosed areas between streets to create new passageways which became important places to socialize and to see and be seen. Now, many of the arcades -- like this one just off of the Grands Boulevards -- have skylights and lots of little shops, boutiques, and restaurants. They're a nice respite from the street where you can still see interesting things.

As the weather gets cooler, the chestnut vendors come out onto the street. They cook the nuts on little grills and keep their apparatus inside an old grocery cart. I haven't seen too many vendors yet, but this one was near the Musee d'Orsay last Sunday. I've never eaten any of the chestnuts, but they smell great.

As the weather gets cooler, the chestnut vendors come out onto the street. They cook the nuts on little grills and keep their apparatus inside an old grocery cart. I haven't seen too many vendors yet, but this one was near the Musee d'Orsay last Sunday. I've never eaten any of the chestnuts, but they smell great.

I visited the Musée du Quai Branly yesterday, and found it an interesting place. It’s one of Paris’ newest museums, and it’s devoted to the art and culture of the non-Western world. Exhibits cover areas in Oceania, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. I think it wants to be a global museum for a global age.

I visited the Musée du Quai Branly yesterday, and found it an interesting place. It’s one of Paris’ newest museums, and it’s devoted to the art and culture of the non-Western world. Exhibits cover areas in Oceania, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. I think it wants to be a global museum for a global age. But the name of the museum speaks to the problem with the collection: it’s not named after its contents, but rather after the street where it’s located. It would be like calling a museum in the US the “Main Street Museum” or the “Poplar Avenue Museum.” The name tells you nothing about what’s inside, only where to find it.

The issue, I think, is the fact that the French have these artifacts from the rest of the world because they colonized all of these places in the nineteenth century. Now that European colonialism is a defunct institution and historians have revealed it as the exploitative and brutal practice that it was, France is faced with a tough question. How to display the items that they took from other parts of the world, sometimes by force, when they ruled these peoples? What do you call a museum that is comprised of the spoils of war and slavery when you’re trying to put a positive spin on it?

So they call it the Musée du Quai Branly because it sits on the Quai Branly near the Eiffel Tower (you can see it in the background of my picture). It’s a beautiful, modern glass and metal structure with a park outside and plants actually growing out of the facade. It wraps you in nature when you enter. Maybe that helps to take the edge off of the story contained -- but not really told -- inside the building.

Here are two unrelated thoughts:

Here are two unrelated thoughts: I pass this candy stand nearly every day at the Place de l'Odeon. The smell of sugar, chocolate, nuts, and other good things fills the air there, and it's sometimes hard to resist. There's a crosswalk just to the left of this stand, and when I'm waiting for the light, I get a little hungry for candy. I haven't bought anything yet, though. There are nearly always people putting their sweets into the little sacks -- it's a popular place. (The man in the picture is one of the people who runs the stand.) I also like the fact that it's so colorful. As Paris gets colder and sometimes a little more grey, having a splash of color on the street is a welcome change.

I pass this candy stand nearly every day at the Place de l'Odeon. The smell of sugar, chocolate, nuts, and other good things fills the air there, and it's sometimes hard to resist. There's a crosswalk just to the left of this stand, and when I'm waiting for the light, I get a little hungry for candy. I haven't bought anything yet, though. There are nearly always people putting their sweets into the little sacks -- it's a popular place. (The man in the picture is one of the people who runs the stand.) I also like the fact that it's so colorful. As Paris gets colder and sometimes a little more grey, having a splash of color on the street is a welcome change.

I saw this scooter on the street a while ago and had to take a picture. Its owner has pasted pictures and words cut out of magazines all over it to create a unique collage (click on the photo to enlarge). It looks like every surface is covered except for the seat and the handlebars. A snazzy way to get around the city.

I saw this scooter on the street a while ago and had to take a picture. Its owner has pasted pictures and words cut out of magazines all over it to create a unique collage (click on the photo to enlarge). It looks like every surface is covered except for the seat and the handlebars. A snazzy way to get around the city.

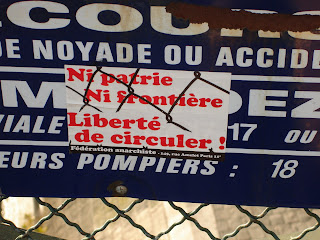

I saw this sticker on the Pont des Arts. It reads "Neither fatherland nor border. Freedom to travel." Posted by the Anarchist Federation, it challenges some of our most cherished notions in the West about the importance of the idea of a "homeland" with well-defined frontiers -- a nation-state that belongs to "us." In an increasingly global economy, people and goods are moving more and more freely across those borders. Yet we also hold onto the notion of differences between peoples.

I saw this sticker on the Pont des Arts. It reads "Neither fatherland nor border. Freedom to travel." Posted by the Anarchist Federation, it challenges some of our most cherished notions in the West about the importance of the idea of a "homeland" with well-defined frontiers -- a nation-state that belongs to "us." In an increasingly global economy, people and goods are moving more and more freely across those borders. Yet we also hold onto the notion of differences between peoples.

Not far from the apartment is Le Tennessee Jazz Bar. I've not been in, and there aren't any signs out front saying who plays there or what kind of place it is. But it struck me as odd since I'm not sure we would use the phrase "Tennessee jazz" in the US. We might talk about Memphis blues, or Tennessee country music. There is jazz in Tennessee, of course, but I'm not sure that "Tennessee jazz" is a unique genre. They probably just thought that Tennessee would be a clever American name to use. The image of the saxophonist on the sign is clearly of an African-American (in a zoot suit, it seems), so maybe they wanted to choose a southern state? But why not New Orleans or Louisiana jazz? Maybe the owner had visited Tennessee at some point in the past.

Not far from the apartment is Le Tennessee Jazz Bar. I've not been in, and there aren't any signs out front saying who plays there or what kind of place it is. But it struck me as odd since I'm not sure we would use the phrase "Tennessee jazz" in the US. We might talk about Memphis blues, or Tennessee country music. There is jazz in Tennessee, of course, but I'm not sure that "Tennessee jazz" is a unique genre. They probably just thought that Tennessee would be a clever American name to use. The image of the saxophonist on the sign is clearly of an African-American (in a zoot suit, it seems), so maybe they wanted to choose a southern state? But why not New Orleans or Louisiana jazz? Maybe the owner had visited Tennessee at some point in the past.